Inclusive Thanksgiving: A Holiday Guide to Supporting Loved Ones With Neurological Conditions

Supporting Family and Friends With Parkinson's, Stroke Recovery, Aphasia, Dysphagia, TBI, and Progressive Neurological Conditions

Thanksgiving represents more than a meal. It's a celebration of connection, gratitude, and togetherness. Yet for families navigating neurological conditions like Parkinson's disease, stroke recovery, aphasia, dysphagia, traumatic brain injury (TBI), dementia, ALS, multiple sclerosis, or other progressive diseases, the holiday can bring unique challenges alongside its joys.

Perhaps this is the first Thanksgiving since your parent's stroke. Maybe your sibling's Parkinson's symptoms have progressed since last year. Whatever your situation, you want to create a holiday that feels warm, safe, and genuinely inclusive. Prepare a Thanksgiving environment that’s not just accommodating for the younger ones but also for the older generations in your home.

This comprehensive guide goes beyond simple menu modifications to address the social, environmental, emotional, and practical aspects of hosting loved ones with speech, language, swallowing, and cognitive challenges. The goal is to help you create a Thanksgiving where everyone feels valued, comfortable, and truly welcomed.

Eating Out for Thanksgiving?

Don’t miss out on the Menu Therapy with Nina series, covering a range of restaurants in South Florida. The series currently covers eight establishments in Lake Worth and Delray Beach. These restaurants are accessible, and they have safe dining options for loved ones with swallowing difficulties.

Understanding the Landscape: Common Conditions and Their Impact

Before diving into specific accommodations, it helps to understand what your loved one might be experiencing. Neurological conditions affect people differently, but common challenges include:

Communication Difficulties

Aphasia (often from stroke) impacts language processing: understanding words, finding words, reading, or writing. Intelligence remains intact, but accessing language becomes difficult.

Dysarthria (common in Parkinson's, MS, TBI) affects the physical production of speech, resulting in slurred, soft, or unclear articulation despite clear thinking.

Apraxia of speech disrupts the motor planning needed to coordinate speech movements, making words come out differently than intended.

Cognitive-communication disorders (from TBI, dementia) may affect organization of thoughts, topic maintenance, or understanding social cues.

Swallowing Difficulties (Dysphagia)

Dysphagia affects the safety and efficiency of swallowing, increasing risks of choking or aspiration (food/liquid entering the airway). It commonly occurs with stroke, Parkinson's, ALS, head and neck cancer treatment, and progressive neurological conditions.

Cognitive Changes

Memory deficits, reduced attention span, slower processing speed, executive function challenges, and difficulty with complex environments can affect participation in holiday activities and conversations.

Physical Challenges

Tremor, rigidity, reduced coordination, fatigue, mobility limitations, and visual changes can impact everything from navigating your home to using utensils at the dinner table.

Understanding these challenges helps us approach accommodations with empathy and purpose.

1. Create an Environment That Reduces Cognitive Load and Supports Participation

Thanksgiving gatherings can unintentionally overload the nervous system of someone living with neurological changes. What feels like “holiday energy” to most people: background chatter, kitchen noise, shifting lights, competing conversations, can quickly become destabilizing for individuals with sensory, motor, or cognitive-communication deficits.

Managing Sensory Input

Many neurological conditions create sensory processing difficulties. What seems like pleasant holiday ambiance to you might be overwhelming stimulation to someone with a TBI or dementia.

Optimize Sound:

Keep one primary sound source at a time (either conversation, music, or TV—not all three).

If your home echoes, soften the acoustics with tablecloths or rugs.

Ask guests to pause side conversations when your loved one is speaking.

Provide a quieter secondary room or patio space where the person can decompress without being isolated.

Support Visual + Spatial Processing:

Use stable, even lighting across rooms to help with depth perception, Parkinsonian visual changes, or post-stroke visual neglect.

Reduce glare from windows or shiny surfaces.

Keep furniture layouts wide and predictable so mobility devices can pass through without obstruction.

Olfactory considerations:

Be mindful that strong scents (perfumes, air fresheners, scented candles) can trigger nausea or headaches in some neurological conditions

Ensure good ventilation if cooking smells become overwhelming

Creating Safe Spaces

Designate a quiet retreat area:

Set up a comfortable room away from main activity

Include a comfortable chair, soft lighting, perhaps soothing music

Let your loved one know this space exists and encourage its use without judgment

Consider it a rest station, not isolation, and anyone can use it

Traffic flow planning:

Keep high-traffic pathways clear of clutter, extension cords, and decorations

Ensure adequate space for walkers, wheelchairs, or those who move slowly

Mark any steps clearly, especially if lighting changes throughout the day

Remove throw rugs that could catch on feet or mobility devices

Temperature and Comfort

Keep the home at a comfortable temperature, as some medications affect temperature regulation

Provide easy access to water throughout the home

Have blankets or sweaters available for those who chill easily

Ensure good air circulation without creating uncomfortable drafts

The Power of Predictability

For individuals with cognitive challenges, memory deficits, or anxiety related to their condition, predictability reduces stress significantly.

Support Predictability + Orientation:

Share a simple written or visual schedule with times for arrival, dinner, dessert, and activities.

Provide a “who’s attending” list, especially for people with memory, TBI, or dementia-related recognition difficulties.

Identify bathrooms, quiet spaces, and seating areas with simple signs or verbal walk-throughs upon arrival.

This kind of environmental support doesn’t “baby” anyone. It empowers participation by reducing the cognitive effort required to simply exist in the space.

2. Facilitating Meaningful Social Connection: Communication Strategies for Everyone

Perhaps the biggest challenge isn't physical accessibility, but rather it’s emotional accessibility. When communication becomes difficult, people often feel isolated even in a room full of family, and isolation from lack of communication can lead to depression. These strategies help everyone connect more effectively.

Universal Communication Principles

Regardless of the specific condition, these approaches support better interaction:

Assume competence:

Remember that communication difficulty doesn't equal cognitive impairment

Speak to adults as adults, never adopting a condescending or childish tone

Presume they understand even if they can't respond quickly

Control your own pace:

Slow down your speech slightly, but not dramatically

Pause between thoughts to allow processing time

Resist the urge to fill every silence

Reduce communication demands:

Ask one question at a time

Keep sentences concise and direct

Break complex topics into smaller parts

Confirm understanding gracefully:

"I want to make sure I understood—you'd like coffee with dessert, right?"

Repeat back what you heard without making it feel like a test

Supporting People With Aphasia

Aphasia disrupts language but not intelligence. The person knows what they want to say but can't access the words, or hears your words but can't process their meaning quickly.

Communication strategies:

Give them time; silence is processing time, not a cue to jump in

Don't finish their sentences unless they specifically ask you to

Offer choices: "Would you like pumpkin pie or apple pie?" rather than "What would you like for dessert?"

Use multiple modalities: gestures, writing key words, showing objects

Keep paper and pen nearby for writing or drawing

Save photos on your phone to help with word-finding (pull up a picture of grandchildren when talking about them)

Ask yes/no questions when appropriate: "Should I get you more water?"

What to avoid:

Speaking loudly (their hearing is fine)

Speaking as if they're not there

Pretending you understood when you didn't

Correcting their word errors unless they request it

Showing frustration or impatience

Helping others interact:

Brief other guests beforehand: "Mom has aphasia from her stroke. She understands everything but has trouble finding words. Give her time to respond, and don't finish her thoughts."

Supporting People With Dysarthria or Soft Speech

These individuals have clear thoughts but difficulty producing clear speech. Their voice may be quiet, slurred, or effortful.

Communication strategies:

Position yourself face-to-face to hear better and see facial expressions

Reduce background noise when they're speaking

Ask them to repeat without showing irritation: "I want to hear this—could you say that again?"

Confirm what you heard: "Did you say you're ready for dinner?"

Let them know when you don't understand—guessing wrong is more frustrating than admitting you missed it

If they have a communication device or letter board, let them use it without commentary

Environmental support:

Seat them away from the noisiest areas

Turn off music or TV when they're talking

Have others stop their conversations to listen

Supporting People With Cognitive-Communication Challenges

TBI, dementia, and some strokes can affect how someone organizes thoughts, stays on topic, or engages in back-and-forth conversation.

Communication strategies:

Keep topics concrete rather than abstract

Gently redirect if they lose the thread: "We were talking about your garden—what did you plant this year?"

Use visual or tactile prompts: show them the photo album you're discussing

Accept tangential stories without correcting

Break activities into single steps

Provide context with each interaction: "I'm going to get the pie now, and I'll bring you a slice"

What helps:

Smaller group conversations (2-3 people maximum)

Familiar topics or shared memories

Activities that don't require sustained verbal exchange

Supporting People With Memory Deficits

Memory loss, whether from dementia, TBI, or other conditions, can make social situations confusing and anxiety-provoking.

Communication strategies:

Introduce yourself warmly each time: "Hi Uncle Joe! I'm Rachel, Tom's daughter. I'm so glad to see you!"

Provide orientation naturally: "We're at my house today for Thanksgiving"

Don't quiz or test: never "Do you remember me?"

Gracefully re-explain without highlighting the repetition

Use photos as memory supports: "This was taken at your 80th birthday party"

Label doors (bathroom, exit) with simple signs or pictures

Creating comfort:

Assign a familiar person to stay nearby

Keep a memory box with meaningful items they can hold and discuss

Accept the same story told multiple times with fresh interest

Redirect rather than correct: if they think they need to go home, validate the feeling ("I know you're thinking about home") then redirect ("but first let's have this delicious pie")

3. Dignified Dining: Beyond Menu Modifications

Thanksgiving dinner is often the centerpiece of the day, but eating with others can feel vulnerable when you have swallowing, motor, or cognitive challenges. Here's how to support comfortable, safe, and dignified dining.

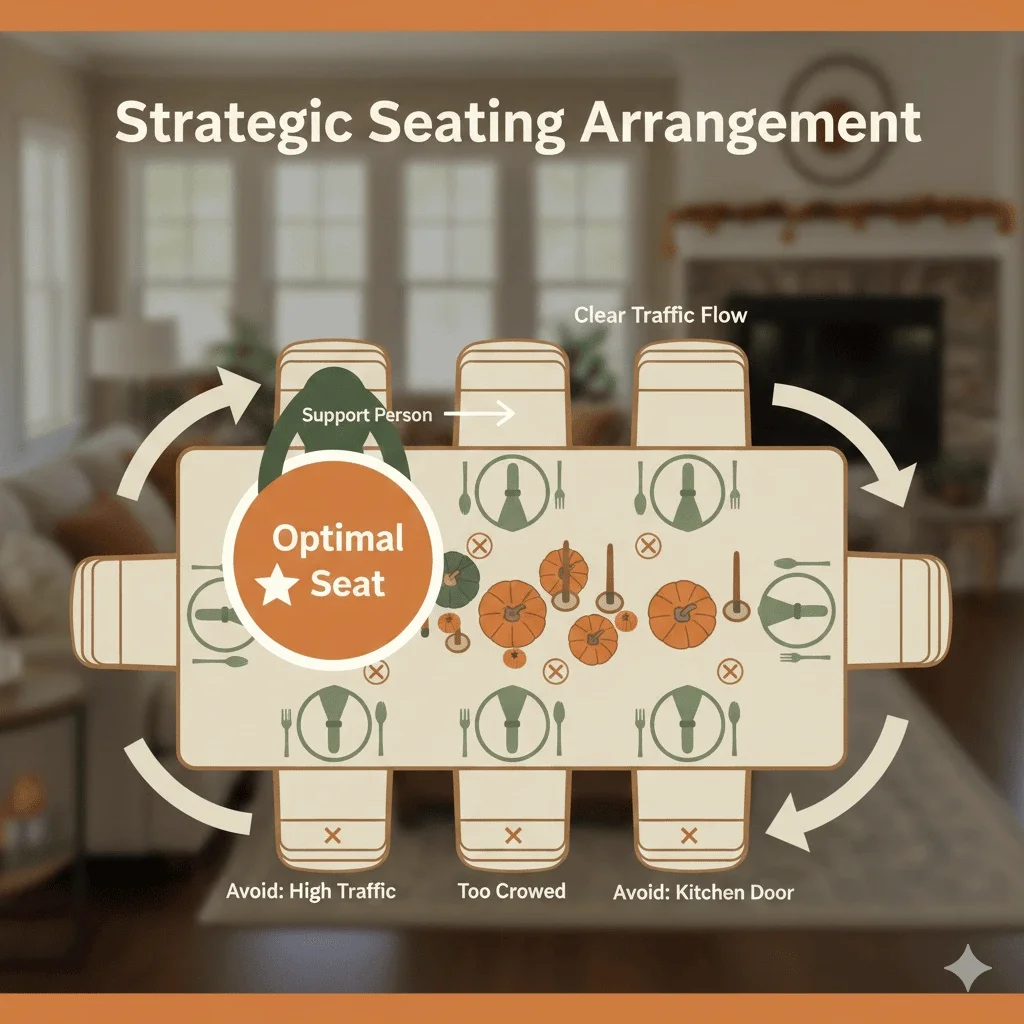

Strategic Seating Arrangements

Where someone sits dramatically impacts their experience.

Optimal placement:

End of the table: reduces visual and auditory overwhelm from both sides

Near a patient, understanding person who knows their needs

Away from kitchen doors, serving areas, and high traffic

With their back to the noisiest part of the room if possible

Close enough to see facial expressions and lip movements

Avoid:

The "spotlight" seat where everyone watches them

Crowded middle positions where they feel hemmed in

Seats requiring them to pass multiple dishes

Adaptive Equipment and Table Setup

Independence at meals preserves dignity. Simple adaptive tools can make enormous differences.

Consider providing:

Weighted utensils for tremor (Parkinson's, essential tremor)

Built-up handles for weak grip or arthritis

Rocker knives for one-handed cutting

Non-slip placemats to stabilize plates

Plate guards or high-sided bowls to prevent food from sliding off

Two-handled cups or cups with lids and straws for better control

Long straws for those who can't lift cups easily

Table setup considerations:

Use real dishes and glasses, not obviously "special" adaptive ware unless requested

Place items within easy reach

Provide adequate space for arm movements

Ensure stable table and chairs (no wobbling)

Serving Strategies That Reduce Pressure

The moment of serving can create anxiety. Remove the pressure. Hopefully, your guest knows how to practice the Lighthouse Method for better awareness at the table, something they may have learned from their SLP.

Options to consider:

Self-service at their pace: Set up the buffet and let them serve themselves without rushing

Quiet kitchen plating: Offer to prepare their plate in the kitchen away from observation

Smaller portions on larger plates: Reduces overwhelm and allows seconds if desired

Family-style serving: Pass dishes individually so they can manage one at a time

For dysphagia specifically:

Pre-cut all foods into appropriate sizes in the kitchen

Ensure moist textures (gravies, sauces readily available)

Provide thickened liquids if prescribed by their SLP

Offer puréed options that look appetizing (use molds, pipe onto plates attractively)

Never announce "this is the special dysphagia meal"—just serve it normally

Creating a Dysphagia-Safe Menu Without Sacrificing Tradition

You can honor tradition while providing safe options.

Naturally dysphagia-friendly Thanksgiving foods:

Mashed potatoes (smooth, moist)

Sweet potato casserole (soft, cohesive)

Well-cooked, moist stuffing

Cranberry sauce

Pumpkin pie (soft, moist)

Mashed or whipped vegetables

Modifications for traditional foods:

Turkey: Choose dark meat, serve with extra gravy, cut small or shred

Vegetables: Cook until very soft, mash or purée if needed

Breads: Serve with butter or dipped in gravy to add moisture

Salads: Skip raw vegetables or provide cooked alternatives

High-risk foods to avoid or modify:

Nuts (choking hazard)

Raw vegetables

Dry bread or crackers

Stringy meats

Mixed consistencies (soup with chunks)

Thin liquids if aspiration risk exists

Dining Pace and Pressure

Allow adequate time:

Start dinner earlier so there's no rush

Let them know they can take as long as they need

Don't clear plates until they're clearly finished

Offer breaks between courses

What never to say:

"You're eating so slowly"

"Just try a little bite"

"Are you going to finish that?"

"Everyone's waiting"

"You didn't eat much"

Understand that coughing may happen:

Mild coughing can be a normal protective response

Don't panic or draw attention unless it escalates

Know the difference between coughing and choking (if choking, they can't cough or speak)

Have the person lean forward slightly and take a break

Keep conversation going to reduce embarrassment

Maintaining Dignity Throughout the Meal

The cardinal rule: Subtlety equals dignity.

Never announce someone's special dietary needs to the table

Don't comment on what or how much they're eating

Offer assistance discreetly: "Can I cut that for you?" in a low voice

If food spills, clean it up matter-of-factly without commentary

Provide cloth napkins that can catch spills more discreetly than paper

4. Activities and Inclusion: Creating Connection Beyond the Table

Thanksgiving lasts longer than dinner. Thoughtful activity planning keeps everyone engaged without creating stress. In fact, many of the PACE activities (designed for communicating with people with aphasia) are fantastic ways to keep a conversation going with most people suffering from some kind of cognitive or language related deficits.

Conversation Approaches That Work

Effective conversation starters:

Memory-based: "What's your earliest Thanksgiving memory?"

Photo-prompted: Bring out old photo albums or scroll through phone pictures

Observation-based: "That's a beautiful sweater—where did you get it?"

Sensory: "This pumpkin pie smells amazing, doesn't it?"

Choice-based: "Which do you like better, cranberry sauce or gravy?"

Conversation structures that help:

Small groups (2-4 people) rather than large table discussions

One topic at a time, explored deeply rather than jumping around

Turn-taking with longer pauses between speakers

Visual prompts (the food, decorations, TV screen) to anchor discussion

Topics that often work well:

Childhood memories

Long-ago holidays

Nature observations (birds at the feeder, fall leaves)

Sports (watching together, not just talking about)

Food memories ("How did Grandma make her stuffing?")

Inclusive Activities for Various Abilities

Low-pressure, communication-light activities:

Watching football or parade together: Shared experience without demanding conversation

Looking through photo albums: Visual prompts support communication

Simple crafts: Coloring, folding napkins, arranging flowers

Listening to music: Perhaps old favorites that spark memories

Gentle movement: Short walk outside if weather permits

Card games with visual elements: Like matching games rather than strategy games

Board games simplified: Adapt rules to reduce complexity

Cooking together: Simple tasks like stirring, pouring measured ingredients

Activity principles:

Should not require fast verbal responses

Can be entered and exited flexibly

Don't have win/lose stakes that create pressure

Allow for varying levels of participation

Provide sensory engagement without overwhelm

Meaningful Ways to Contribute

People want to feel useful, not just accommodated. Find genuine ways they can participate.

Kitchen contributions:

Washing vegetables

Stirring (with supervision if needed)

Taste-testing

Arranging items on serving platters

Folding napkins

Setting silverware

Hosting contributions:

Greeting guests at the door

Showing guests where to put coats

Holding the baby (if appropriate)

Sharing a memory or saying grace

Choosing music

Lighting candles (with supervision)

The key: Make it real participation, not "busy work." If they're stirring the gravy, actually use that gravy.

Respecting Energy Levels and Rest Needs

Neurological conditions often bring profound fatigue.

Normalize rest:

"There's a comfortable chair in the den if you'd like a quiet spot"

"Would you like to rest before dessert?"

"No need to stay the whole time—we're just glad you're here"

What not to do:

Call attention each time they step away: "Are you okay? Where are you going?"

Insist they stay for everything: "But you'll miss the game!"

Make them feel guilty: "You're leaving already?"

Hover anxiously: "Do you need to lie down? Are you feeling sick?"

Empower choice:

"Stay as long as you're comfortable"

"You can rest in the guest room anytime"

"Some people will be here late, others will leave early—whatever works for you"

5. Navigating First Encounters: When This Is Your First Time Seeing Their Changes

Perhaps the hardest Thanksgiving is the first one after a major change. It could be the first since the stroke, the first since the Parkinson’s diagnosis, the first time you're seeing how much the condition has progressed, but it won’t be easy.

Preparing Yourself Emotionally

Acknowledge your feelings privately:

It's okay to feel sad, shocked, or anxious

Process these emotions before the gathering, not during

Talk to someone who understands

Remember: your loved one is still themselves

Set realistic expectations:

They may look different, sound different, or act differently

Focus on who they are, not who they were

Celebrate what remains, don't mourn what's changed

This may feel hard, and that's okay

The First Interaction

Lead with warmth and normalcy:

Greet them as you always have (hug if that was typical, wave if not)

Use a natural, upbeat tone

Make eye contact

Smile genuinely

What to say:

"I'm so happy to see you"

"I've been looking forward to today"

"You look great"

"How was the drive?"

What never to say:

"Oh my God, you look so different"

"I can't understand what you're saying"

"Do you remember me?"

"This must be so hard for you"

"You used to be so [talkative/active/sharp]"

Throughout the Visit

Mirror their pace and energy:

If they're quiet, be comfortable with quiet

If they speak slowly, slow your own speech slightly

If they seem tired, don't push for engagement

Match their communication style

Validate without pitying:

"Take your time" (not "I know this is hard for you")

"I'm listening" (not "I'm sorry you can't talk well")

"Would you like some water?" (not "You must be so frustrated")

Focus on connection, not performance:

You don't need perfect conversation

Sitting together in comfortable silence counts

A smile, a touch on the arm, being present—these matter most

Supporting Communication Tools Without Commentary

If your loved one uses AAC (augmentative and alternative communication) devices, communication boards, text-to-speech apps, or writing to communicate:

Do:

Wait for them to finish using their tool

Read what they've written or listen to what the device says

Respond naturally as if they'd spoken

Treat the tool as you would glasses or a hearing aid—normal adaptive equipment

Don't:

Comment on the tool: "Wow, that's interesting" or "That's so cool"

Ask questions about how it works during conversation

Talk about them to others while they're using it: "Hold on, she's typing"

Act impressed or pitying

Grab the device to "help"

6. Safety Considerations: Discreet Vigilance

Safety matters, but over-monitoring strips dignity. The goal is unobtrusive awareness.

Dysphagia Safety

Before the meal:

Confirm with caregivers any dietary restrictions or texture modifications

Have thickening powder available if needed

Know the person's specific swallowing precautions

During the meal:

Ensure they're seated fully upright (90° angle)

Provide appropriate textures and sizes

Allow plenty of time

Keep conversation relaxed so they're not rushed

Recognizing problems:

Coughing during/after swallowing may indicate material entering the airway—have them stop eating and take a break

Wet vocal quality after swallowing suggests residue

Pocketing food in cheeks needs gentle reminder to clear

True choking = cannot cough, speak, or breathe—know Heimlich maneuver

Response protocol:

Stay calm—panic escalates situations

Have the person lean forward slightly

Encourage deliberate coughing if able

Offer small sips of water only if they're not actively coughing

If choking occurs, act immediately but calmly

Have caregiver's emergency plan accessible

Parkinson's-Specific Safety

Mobility challenges:

Freezing episodes: The person suddenly can't initiate movement. Offer your arm for stability, don't pull or push. Sometimes rhythmic cues help: counting "1-2-3" or humming.

Rising from chairs: Ensure chairs have arms; give extra time; let them initiate the movement

Walking: Clear paths of obstacles; adequate lighting; offer arm if needed

Turning: Wide turns reduce fall risk; don't rush

Medication timing:

Parkinson's medications are time-sensitive

Don't let festivities delay medication schedules

Have a private, quiet place for medication administration

Tremor management:

Weighted items help

Never comment on tremor or watch them struggle

Offer help pouring or cutting discreetly

Cognitive and Memory Safety

Environmental safety:

Supervise around stoves, candles, sharp objects, but subtly

Lock doors if wandering is a concern

Ensure bathrooms are clearly labeled

Remove valuable or dangerous items to storage

Social safety:

Brief guests on topics to avoid (recent losses they may not remember, for example)

Redirect gracefully if they share inappropriate information

Don't correct errors that don't matter

Step in if they seem distressed or confused

Medical emergencies:

Know their medical history and emergency contacts

Have their medication list accessible

Know location of nearest emergency room

Brief one responsible person on any specific concerns

General Safety Principles

Plan ahead: Anticipate needs before they become emergencies

Assign point person: One family member knows the full safety plan

Communicate discreetly: Use text or private conversation for safety concerns

Respect autonomy: Don't over-protect; allow calculated risks

Know limits: If safety can't be ensured, smaller gatherings may be better

7. Supporting the Caregiver: The Often-Forgotten Guest

Behind every person with a neurological condition is often a caregiver who's exhausted, stressed out, and still trying to do their best to enjoy the holidays. Don't forget them.

Understanding Caregiver Reality

Caregivers often:

Haven't had a break in months

Feel responsible for everything going well

Worry constantly about their loved one's comfort and safety

Neglect their own needs

Feel isolated even in social situations

Carry guilt about feeling burdened

Need support but don't know how to ask

Concrete Ways to Help

Before Thanksgiving:

"What can I prepare that would make things easier for you?"

"Should I pick you both up so you don't have to drive?"

"What specific accommodations does [name] need?"

"Is there anything you need me to brief other guests about?"

During Thanksgiving:

"I'd love to sit next to [name] during dinner—you should eat without worrying"

"I'll help with [name's] plate"

"Why don't you take a break? I'll keep [name] company"

"Go ahead and chat with everyone—I'll stay here"

Offer to help with mobility or bathroom assistance

Step in for the loud or overstimulating activity they'd normally manage

What caregivers need most:

Permission to step back and enjoy themselves

Someone else to be vigilant for an hour

Acknowledgment of what they do

Not to be asked "How are you holding up?" in front of their loved one

Genuine offers, not vague "let me know if you need anything"

What Not to Do

Avoid:

Giving unsolicited advice: "Have you tried...?" or "My friend's mother did..."

Comparing situations: "My aunt had that and she..."

Questioning their decisions: "Are you sure they should be eating that?"

Creating more work: "You should really do [additional thing]"

Putting them on the spot: "Tell everyone about the diagnosis"

Long-Term Support Conversation

Thanksgiving might be the time to gently open longer-term support conversations:

"I'd love to give you a regular break—could I come over every Thursday?"

"Can we set up a meal train for your family?"

"Would it help if I researched respite care options?"

"Let's find a support group that might work for you"

But never during the gathering itself. Wait for a private moment or follow up later.

8. The Overarching Principle: Dignity, Always Dignity

Every recommendation in this guide serves one central purpose: preserving dignity while providing support.

What Dignity Looks Like

Dignity means:

Being treated as a complete person, not a collection of deficits

Having choices respected

Not being the center of worried attention

Participating meaningfully in family traditions

Maintaining privacy about personal challenges

Not being discussed as if they're not present

Having limitations accommodated subtly, not spotlighted

What Dignity Doesn't Mean

Dignity is not:

Pretending nothing has changed

Avoiding all mention of their condition

Over-helping to the point of infantilization

Forced independence when help is needed

Unrealistic expectations that set them up to fail

Dignity in Practice

Ask yourself before each interaction:

Would I want someone to treat me this way?

Am I solving a real problem or my own discomfort?

Am I helping them participate or managing them?

Does this preserve their autonomy?

Would this feel patronizing to me?

The Gold Standard

If your loved one leaves Thanksgiving feeling:

Welcomed, not accommodated

Connected, not isolated

Valued, not pitied

Like themselves, not their diagnosis

You've succeeded.

9. After Thanksgiving: Reflection and Ongoing Support

The holiday ends, but the relationship continues.

Follow Up Thoughtfully

Within a few days:

Send a photo from the day

Thank them for coming

Mention a specific moment you enjoyed with them

"I loved hearing your story about Thanksgiving in the '70s"

Be specific in your gratitude:

Not: "Thanks for coming"

But: "Having you there made it feel like Thanksgiving"

Learn and Adjust

Reflect on what worked:

What accommodations were most helpful?

What could be improved next time?

What did they seem to enjoy most?

Were there moments of visible discomfort?

Ask the caregiver (privately):

"How do you think [name] did with everything?"

"What could I do better next time?"

"Were there any stressful moments I didn't catch?"

Maintain Connection

The biggest gift you can give isn't perfect Thanksgiving accommodation—it's ongoing relationship.

Throughout the year:

Regular calls or visits (adapted to their communication style)

Including them in family updates and photos

Remembering they're still interested in your life

Not disappearing because communication is harder

Asking about their interests, not just their condition

Remember:

They're still the person who taught you to fish

Who made you laugh at family dinners

Who showed up to your graduation

Whose voice you recognize even if it sounds different now

The condition changed some things. It didn't change everything.

10. Resources for Continued Learning

Supporting loved ones with neurological conditions is an ongoing journey. Here are pathways for deeper understanding:

Professional Organizations

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA): Resources on aphasia, dysphagia, and communication disorders

National Aphasia Association: Support for people with aphasia and their families

Parkinson's Foundation: Education, support groups, and care resources

American Stroke Association: Recovery resources and caregiver support

Brain Injury Association of America: TBI-specific guidance

Finding Local Support

Search for speech-language pathologists specializing in neurological conditions

Look for local support groups for specific diagnoses

Investigate respite care services for caregivers

Connect with hospital or rehabilitation center social workers

Check community centers for adaptive programs

Educational Resources

Online aphasia communities and conversation groups

Dysphagia cookbooks and recipe modifications

Communication apps and AAC tools

Caregiver training workshops

Dementia care certifications for family members

Final Thoughts: The Heart of Thanksgiving

At its core, Thanksgiving celebrates gratitude, connection, and belonging. When we accommodate loved ones with neurological conditions thoughtfully and respectfully, we're not just solving logistical problems, we're affirming their place at the table and in our hearts.

Your loved one may communicate differently now. They may need different foods, different pacing, different support. But their fundamental humanity, their relationships, their belonging…these haven't changed.

This Thanksgiving, you have the opportunity to create omething truly meaningful: a holiday where everyone feels they belong exactly as they are.

That's the greatest gift you can give.

Happy Thanksgiving to you and yours.

Contact Nina for In-Home Speech Therapy Services Across Palm Beach County

If this Thanksgiving brought new awareness to a loved one’s communication, memory, voice, or swallowing challenges, you don’t have to navigate the next steps alone.

Worried about family after this Thanksgiving? Check up on the early signs of dementia as told through anecdotes as well as a checklist for noticing when loved ones might need dementia help.

Palm Beach Speech Therapy provides compassionate, evidence-based in-home support for adults recovering from stroke, Parkinson’s disease, aphasia, dysphagia, dementia, TBI, and progressive neurological conditions. Nina helps families throughout Lake Worth, Boynton Beach, Delray Beach, Palm Beach, and the surrounding areas.

If you’d like guidance, an evaluation, or individualized therapy for your loved one, we’re here to help.

📞 Call: (561) 797-2343

📧 Email: ninaminervini11@gmail.com

📝 Contact Form

Support is available year-round, with care that meets your family right at home.

This guide is intended for informational and educational purposes. Always consult with healthcare providers, speech-language pathologists, and other specialists for individualized recommendations for your loved one's specific needs.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. How can I prepare my home for a loved one with stroke, needs help with Parkinson’s, or dementia before Thanksgiving?

Focus on safety and sensory comfort. Clear clutter from walkways, create wide paths for walkers and wheelchairs, provide good lighting in halls and bathrooms, and set up a quiet retreat space away from noise. Share a simple schedule for the day so your loved one knows when guests arrive, when you’ll eat, and where they’ll sit.

2. What are some easy ways to support communication during holiday gatherings?

Speak face-to-face, reduce background noise, and give extra time for responses. Use simple language, ask one question at a time, and offer choices instead of open-ended questions. Visuals—such as photos, written key words, or a simple communication board—can help people with aphasia, cognitive-communication changes, or soft speech participate more comfortably.

3. How can I make Thanksgiving dinner safer for someone with dysphagia or swallowing problems?

Follow the recommendations from your loved one’s speech-language pathologist about food textures and liquid thickness. Offer moist, easy-to-chew foods, cut items into small pieces, and avoid high-risk textures like nuts, tough meats, and dry bread. Seat the person upright, allow plenty of time to eat, and never pressure them to “just try a bite.”

4. What should I do if my loved one coughs while eating during the holiday meal?

Mild coughing can be a normal protective response. Encourage them to pause, clear their throat, and take a break before continuing. If coughing, choking, or breathing difficulty persists or worsens, stop the meal and follow their healthcare provider’s instructions. Seek emergency care right away if they cannot cough, speak, or breathe.

5. How can I include a loved one with memory loss or dementia without overwhelming them?

Keep the environment calm, use a small group setting when possible, and reintroduce yourself warmly as needed. Visual schedules, labeled rooms (such as “Bathroom” or “Kitchen”), and familiar activities—like looking through old photos or watching a favorite game—can help. Allow them to rest when needed and avoid correcting harmless mistakes or memory gaps.

6. When should we consider speech therapy for communication or swallowing changes we notice around the holidays?

If you see ongoing changes in speech clarity, word-finding, memory, or swallowing—such as frequent coughing during meals, avoiding certain foods, or difficulty following conversations—it’s a good idea to talk with your loved one’s doctor. A physician can refer to a speech-language pathologist for a formal evaluation and individualized treatment plan.